PAINTERS OF THE NIGHT

Artists played a central role in the evolution of our cultural perception of night. In early America, long-held superstitions associated the night with concealing sinister and dark actions. Early 19th century artists responded by creating nocturnal paintings that harnessed the collective fear of what lurked in the dark. The increased industrialization following the Civil War created a demand for artificial lighting that was brighter, safer, reliable and more affordable. Innovations in artificial lighting technology illuminated the night and extended the day.

Electric arc lighting, kerosene carriage lamps, and streetlights allowed people more mobility after dark and the chance to gather for leisure and commercial pursuits. Artists used new techniques – such as rapid brushwork, bright colors and thick paint layers – to depict cityscapes and street scenes that captured the vibrancy of the illuminated night. By the end of the 19th century, the superstitious belief of night as ominous had evolved into the perception of night as the realm of social entertainment and leisure.

Proctor Collection, PC. 564. Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Museum of Art, Utica, NY

LIGHTING TECHNOLOGY

Artificial lighting did more than brighten the American night. It dictated new interior design strategies and contributed to shifting beliefs about domestic space. Interior design and etiquette books suggest the important role of lamplight on how a room was furnished. Bestselling authors like Clarence Cook and Oswego-born Julia McNair Wright wrote books that offered advice for the placement of lamps according to a room’s public, private, or utilitarian function. Each lamp fuel source lit the dark at different levels of brightness and shades of color. The qualities of light unique to each lamp type impacted the perception of color and space as well as the mood of a room. Variables such as smell, sound, smokiness, and movement of the flame added subtle nuances to a room’s design.

Decorative artists and fashion designers began choosing materials and decorative elements with artificial lighting sources in mind. Designers considered the reflective impact of their designs for jewelry, clothing, fans, purses, rugs and furniture. Materials that reflected, sparkled or amplified light became popular as expressions of wealth, status and modernity.

PAINTERS OF LIGHT

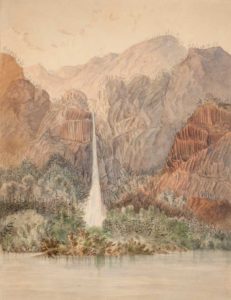

Hudson River School artists such as Thomas Cole and Francis Silva spent their summers touring and sketching scenic destinations throughout the Northeast. However, their aim was not to produce accurate depictions of the natural world. As some preliminary works on display illustrate, they made preparatory sketches in the field to detail specific trees, rocks, plants and water features. Later, in their New York City studios during the dark days of winter, the Hudson River School artists blended these sketches into idealized landscape compositions. Their approach to light was more theatrical and symbolic than authentic.

The mid-19th century brought technical and industrial advancements that would impact the art world. Expanding railroad lines made it easier for artists to travel to such natural wonders as Niagara Falls and the American west. Art supply firms produced lighter weight academy boards and collapsible field stools, easels and umbrellas. Most significantly, American artist John Rand invented the portable paint tube in 1841. This freed artists to paint rather than sketch outdoors and depict different seasons, weather, times of day and natural lighting conditions. As artists’ scientific understanding and perception of light evolved, this knowledge informed the way that they painted.

French Impressionism emerged in the 1870s and took less than a decade to take root in America. Impressionists abandoned rigid technique and contrived subjects. Instead, they focused on light as a subject matter and how it changed our perception of color and form. Portable tools enabled the execution of quickly painted canvases, “impressions” of the surrounding natural world, with a truthful spontaneity. Rapid brushwork, thick paint layers, and unorthodox color pairings helped distinguish Impressionism from all earlier movements. They embodied modernization and represented the technical advancements of the 19th century.